Background: Problems with assumptions for 3D editors

3D editors today feel way too encumbered by modes of editing. Working with primitives is more cumbersome than it needs to be.

You’re usually expected to:

plan ahead before you make a shape

e.g. make 2D representations of an object from different orthographic perspectives

switch between at least a dozen modes where you can manipulate only one single thing at once (e.g. rotate object, move object, scale object, move face, move edge, move vertex, create cube, create cylinder, etc.)

Let’s address these assumptions.

Main inspiration - the importance of being able to see what you’re doing for creativity

Not having to plan ahead

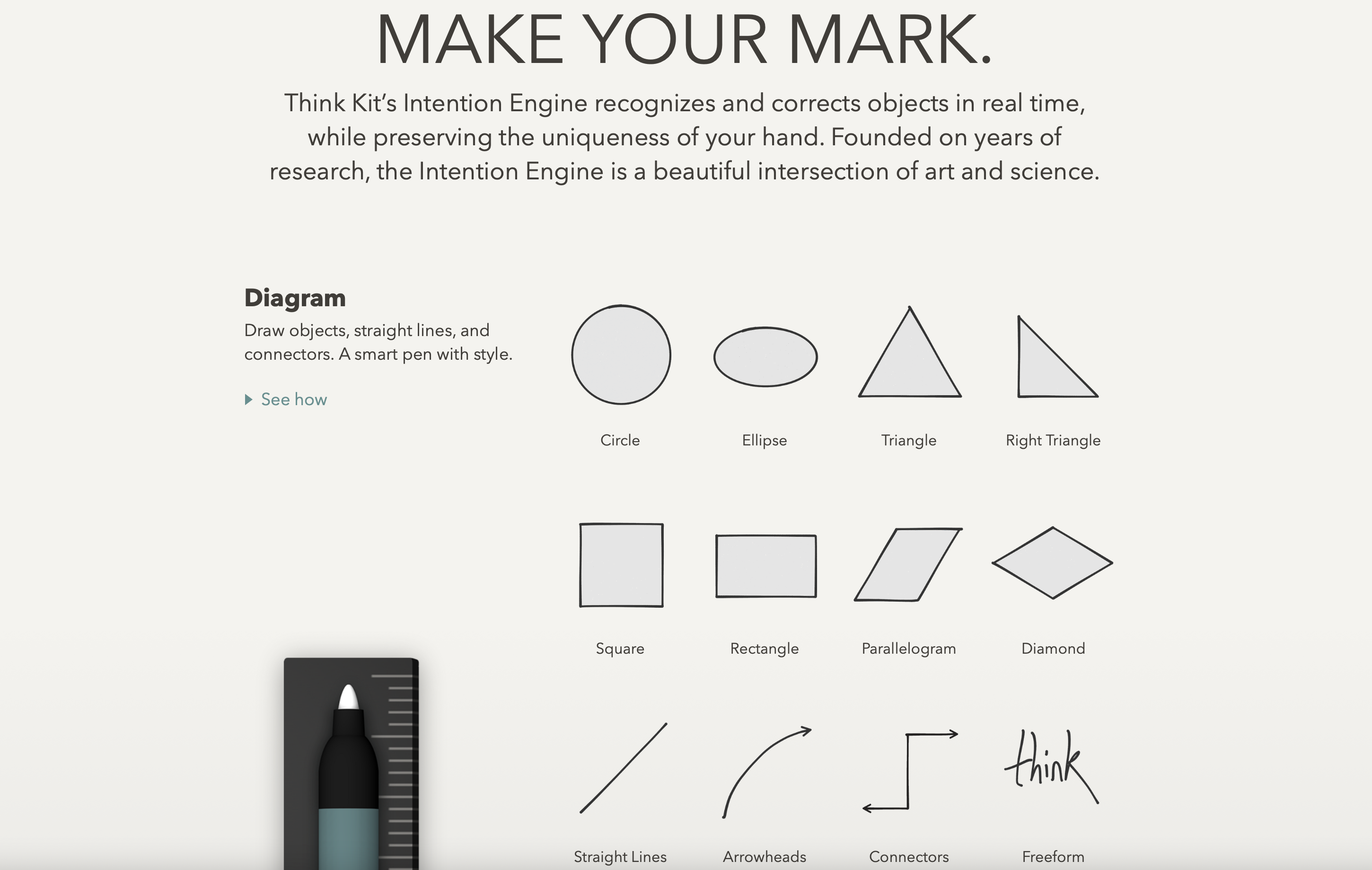

In the iOS app Paper (formerly by FiftyThree which is now acquired by WeTransfer), there are tools which allow you to very easily draw and manipulate shapes.

You can draw an outline of a square, circle or other shape and it will immediately snap into place. It can be drawn with Apple’s stylus (Apple Pencil) and easily moved around with your finger.

(I believe that resizing and rotating have also been added, but I’m on a much older version of the app, for nostalgia reasons with FiftyThree’s stylus.)

It is very easy to join shapes to create bigger figures too.

This is a quick demonstration of me creating a 2D robot-like figure, by drawing overlapping shapes:

This diagramming feature on Paper was released as part of their Think Kit update long ago in 2015. From various quotes on that now archived page:

Mobile whiteboarding at the speed of thought.

Paper inspired an entire way of working for us—this kind of lightning-fast capture of what you’re really thinking.

Keith Yamashita (Chairman & Founder, SYPartners)

FiftyThree founder and CEO Georg Petschnigg did give a small hint about how it hopes Paper will stand out through predictive technology. "When you're working on a mobile device, you always have to tell it what you want to do before you can do it. Open a keyboard to type. Grab a shape or a pen tool to draw," he said. "We want to make it possible to create with a fluid ease, without having to prompt the computer first."

Source: The Verge

What really captures me still with Paper even today is that you can draw an idea as fast as you think it, as they say. Paper remains unbeatable and unparalleled in that regard for me for digital drawing.

The other time I felt that I had this experience with making things on iPad this fast – at the speed of thought – is when I used to code on an app called Hopscotch as a teenager. I could basically sketch out 2D coded apps/games/drawings as fast as I had the idea, by quickly dragging out blocks from a palette and testing the idea.

I’d be inspired by a maths equation (like adding a sine wave with a linear equation) in a maths exam. And boom like that night or so, I’d have a coded art project using that.

The interface for Hopscotch has changed since then so it’s not as responsive as it used to be. (I’m saying this even though I have worked there, for disclosure.) And it isn’t necessarily the fastest example of being able to iterate, because you can’t edit projects while they’re running. (Squeak Etoys is able to do that, way back.)

As for why this is important, the computerist/electrical engineer/interface designer Bret Victor summed it up in a well-considered piece on Learnable Programming:

CREATE BY REACTING

I was recently watching an artist friend begin a painting, and I asked him what a particular shape on the canvas was going to be. He said that he wasn't sure yet; he was just "pushing paint around on the canvas", reacting to and getting inspired by the forms that emerged. Likewise, most musicians don't compose entire melodies in their head and then write them down; instead, they noodle around on a instrument for a while, playing with patterns and reacting to what they hear, adjusting and sculpting.

An essential aspect of a painter's canvas and a musical instrument is the immediacy with which the artist gets something there to react to. A canvas or sketchbook serves as an "external imagination", where an artist can grow an idea from birth to maturity by continuously reacting to what's in front of him.

Programmers, by contrast, have traditionally worked in their heads, first imagining the details of a program, then laboriously coding them.

Working in the head doesn't scale. The head is a hardware platform that hasn't been updated in millions of years. To enable the programmer to achieve increasingly complex feats of creativity, the environment must get the programmer out of her head, by providing an external imagination where the programmer can always be reacting to a work-in-progress.

Imagine if you were building in Minecraft (3D voxel editor game) and whenever you wanted to place or remove a block, you would have to stop everything else from running (e.g. gravity, mobs attacking) and restart the system afterwards.

That is basically how we treat today’s programming systems at the moment, unfortunately, by the way. And other things. (In the 70s, the language and system Smalltalk was written in itself and you could edit the system while it is live. Smalltalk derivatives still exist today, like Pharo.)

This runs into the next assumption about having modes for editing and playing, as well as having a mode for every single editing action.

Modeless Editing

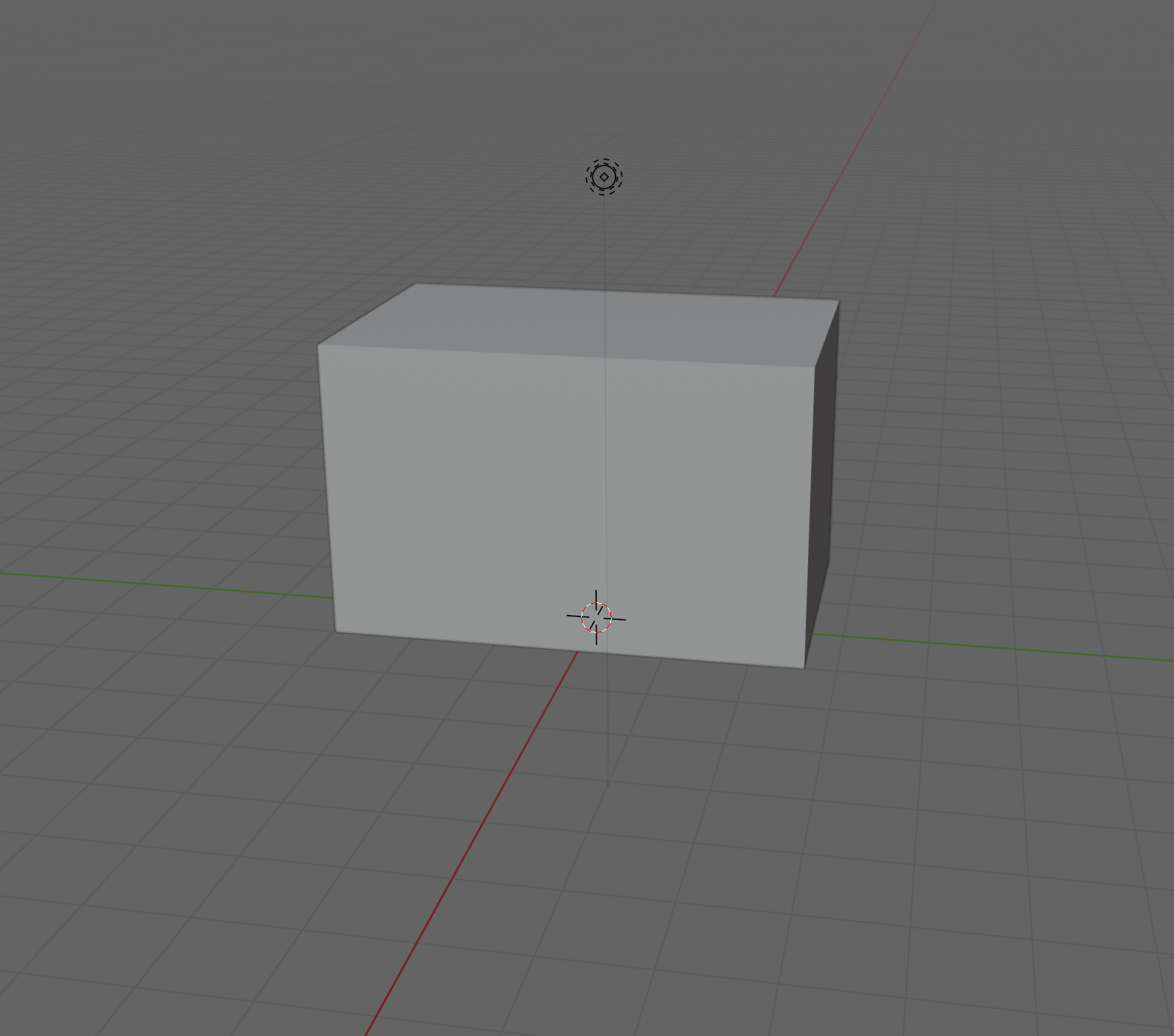

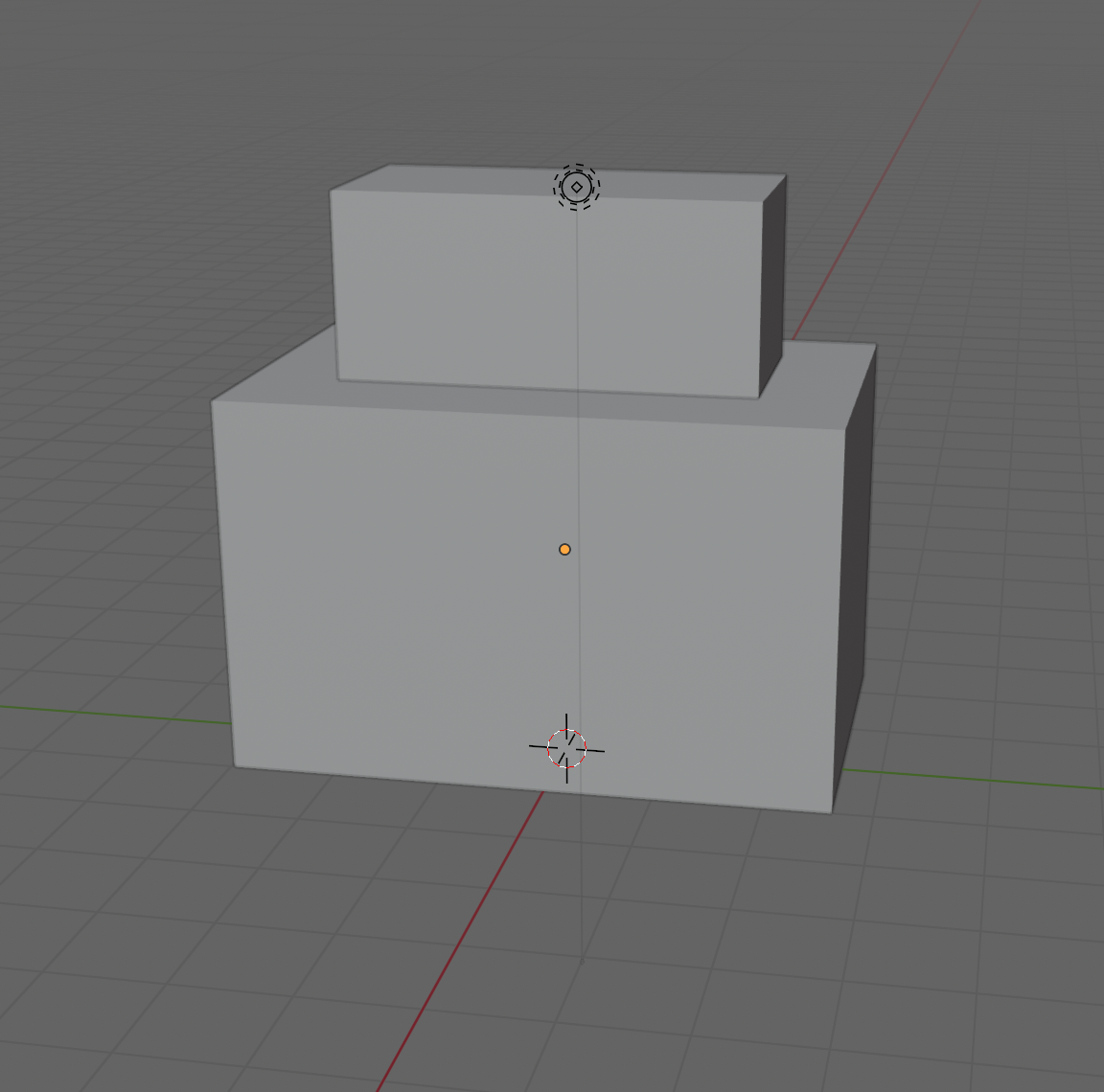

It seems like such a simple task, the small robot-like figure I made in Paper. Imagine if it was that simple and effortless to create that object in 3D (with cubes and spheres).

But if you were to do that in a 3D editor, you’d usually have to do something like this:

- switch to cube tool

- place cube

- switch to sphere

- place sphere

- switch to move tool

- move sphere to align with cube

- combine objects

- create cube

- switch to edge mode

- resize edges to turn into prism

- move prism

- etc.

In the 2D drawing app, I did switch between their diagramming and fill tools for colouring. But I didn’t have to switch between anything for drawing squares vs. rectangles vs. circles.

I did that video in 1 min with several mistakes (where the app wasn’t recognising my 3-sided incomplete rectangles).

You might be able to do that in 1 min if you work daily with 3D editors and have the keyboard command modes in your muscle memory. But for an unpracticed user, I don’t think you could do that in 1 min in a 3D editor.

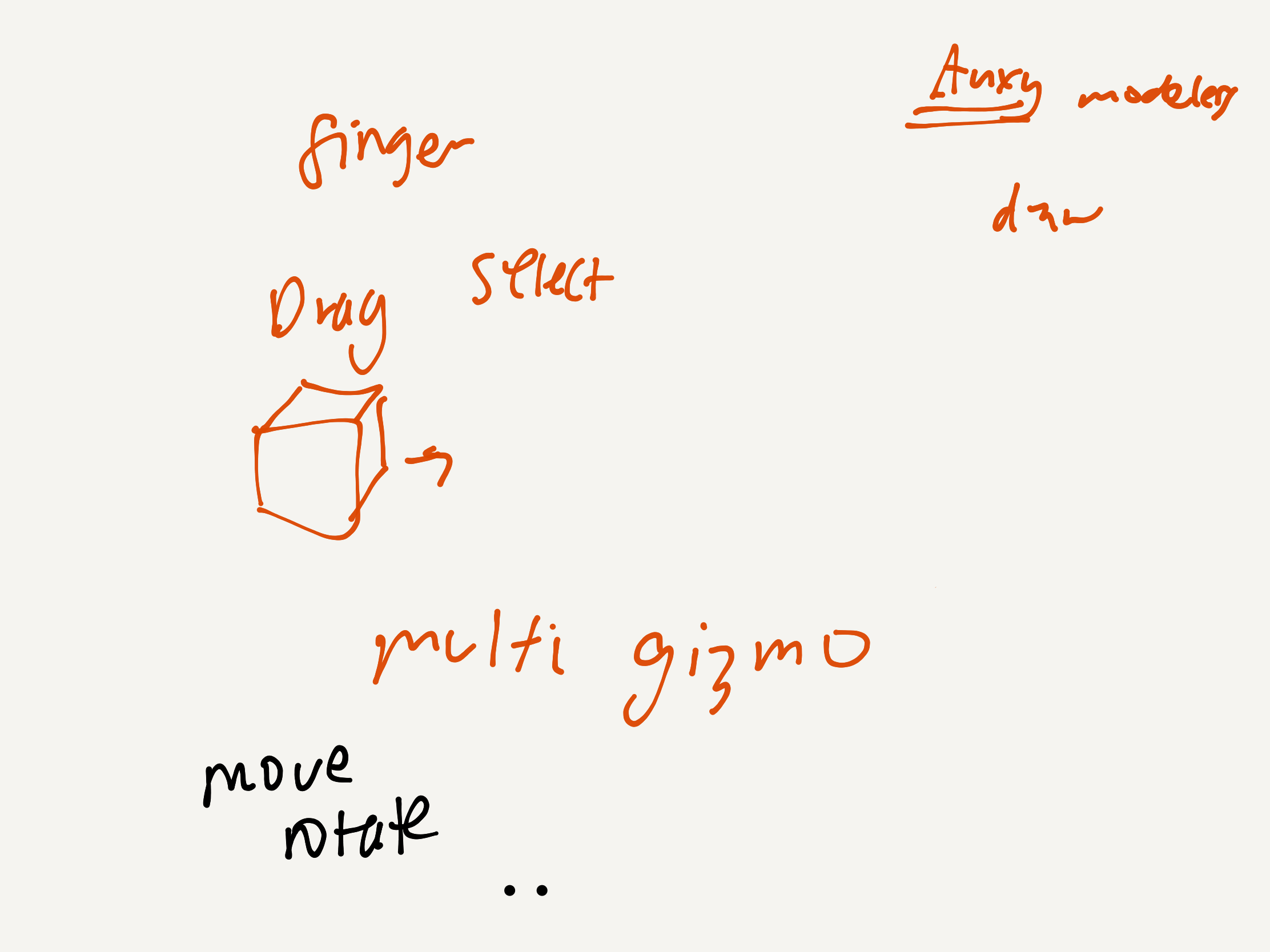

The iOS music app Auxy, among many others, allows you to edit the music notes while the project is playing. This allows you adjust and change notes — melody, chords, basslines, percussion, you name it — much faster, since you can do it right while you’re listening to it. Another thing that Auxy does is that it doesn’t lock you into fully separate modes for adding, selecting, moving and deleting notes, and panning to scroll, which some other apps do.

The idea of modeless editing is best summed up by computing pioneer Alan Kay (designer of Smalltalk) in many places. For example, this is from a paper on Squeak Etoys:

The User Interface Ideas Are Few and Simple

We are used to modeless editing of text, but most applications have an “editing mode” and a “presentation mode”. Within these are “button modes”, “background-foreground modes”, etc. Squeak eliminates virtually all of these. For example, all editing can be done at any time in full-screen and even while running as a plug-in in a browser. The way objects are selected allows even event-sensitive objects like buttons to be manipulated even while they are “live”.

Balloon Help Is Always Active (But Delayed)

Balloon Help is usually disabled in today’s systems because it is so intrusive. We have found that a 1.5 second delay provides a nice balance. A confident and knowledgeable user will never see it, but it is always active and provides consid- erable aid to beginners. The user can edit the balloon help to add helpful notes for themselves and others.

The Halo of Handles

Every object will show the same “halo of handles” that allow efficient invocation of the most used manipulations, such as: rotation, scaling, copying, etc. It is possible to choose a filter to limit which ones show up for beginners (but we have found that all beginners have no trouble at all with the full suite of handles right from the beginning).

The Handles Are Also Squeak Etoys Objects

(Everything is.) This means that end-users have the option of customizing everything in the system. Most of the time this will not be done, but e.g. for young children, a teacher may wish to add more extensive notes to the existing balloon help, or make the handles appear quicker. Squeak has “fences” that warn about changes and entering more complex territories, but the end-users can still have the option to explore.

Having the halo with all manipulation options available at once means that the user doesn’t have to switch between “only moving“ or “only resizing”. They can drag handles to move and resize, and do other things in between, without locking themselves into only one of those modes.

Kay also explains this when referring to GRAIL (GRAphical Input Language), back in 1987 in his talk Doing With Images Makes Symbols:

Another thing that was going on at Lincoln Labs was the first iconic programming. It was done at RAND corporation, the people who did the wonderful interactive programming language JOSS. It was for done for economists and non-computer specialists at RAND who had to compute. And one of their complaints about — really, their only complaint about JOSS was they said, “hey, none of us can type. Can’t you do something about that?”

So that let to the invention of the first data tablet. It was called the RAND tablet back then. And this system, from about 1968, called GRAIL for GRAphical Input Language.

No keyboard, whatsoever. It recognized he wanted a box and made one.

Now it's recognizing his hand-printing.

He wants to change the size of the window. Here's where McIntosh window control came from literally.

Notice that every command is not just iconic, but also analogic.

And by that I mean that it looks like the thing that you want.

So if you want to scrub something out, you scrub it out. If you want to draw a box, you just draw a box. It recognizes he wants one, it makes one the same size.

Chop off a corner. And label it subscan. You want characters — you just make characters, and it recognizes those. There are no menus to reach to. You're always looking directly at where you're working, and notice it missed the n at the end of sub scan there.

He saw. He hesitated, but it's the world's first modeless system, so he's able to just go and change it without issuing any more commands. You see every command that's actually being issued, and they're all in the form of direct action.

Complete the diagram from scan to post. What a remarkable system that was.

And when I saw that, I felt and used it for half an hour in 1968. I felt like I was sticking my hands right through the display and actually touching the information structures directly.

This is the first system I'd ever used and practically the only one since that I've called truly intimate, and it was this degree of intimacy that is so important in a user interface.

I used to show this movie to my group at Xerox PARC every three months or so we wouldn't forget what we're trying to do.

Other options

From Croquet: A Menagerie of Interfaces

Direct manipulation

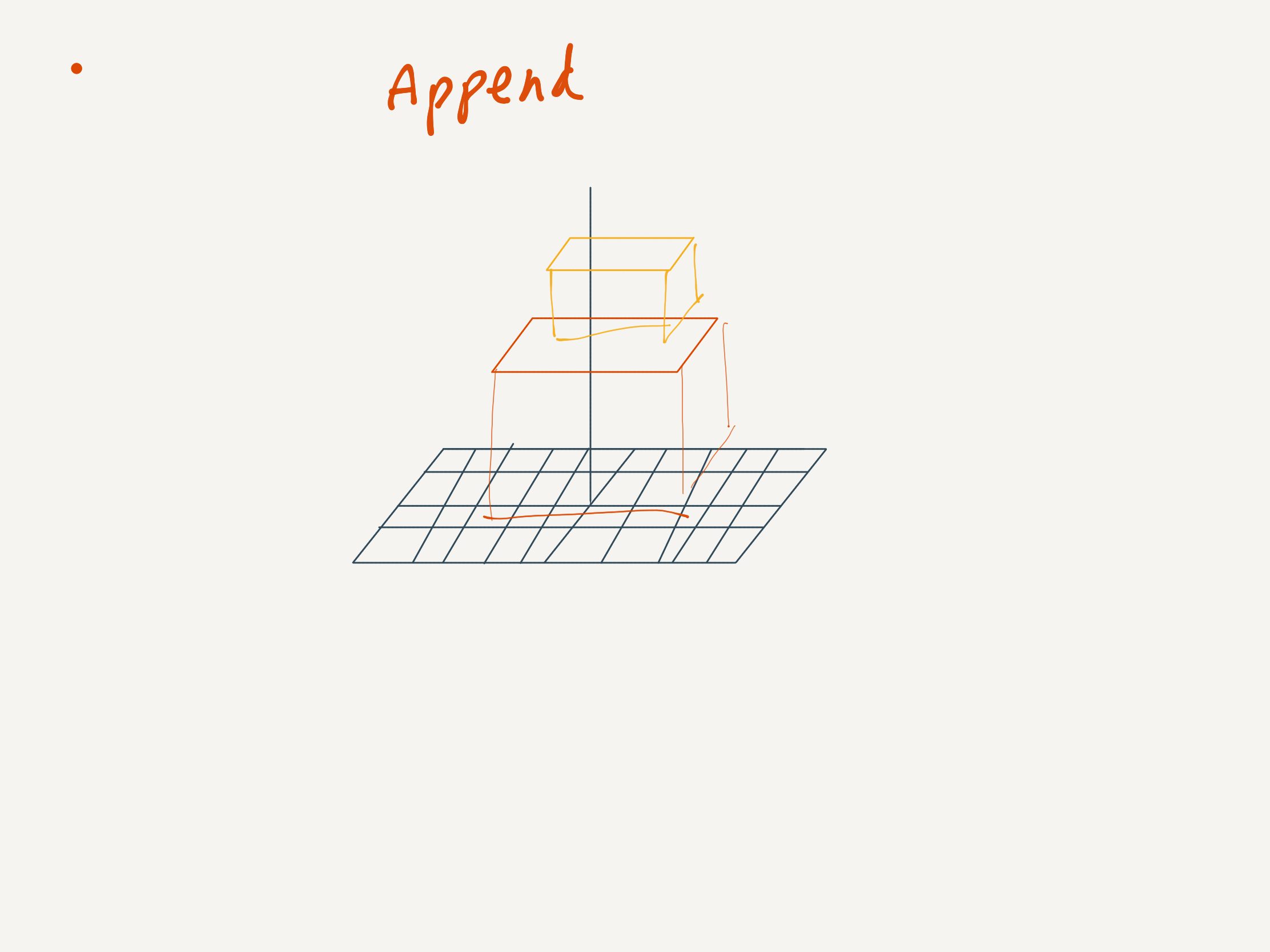

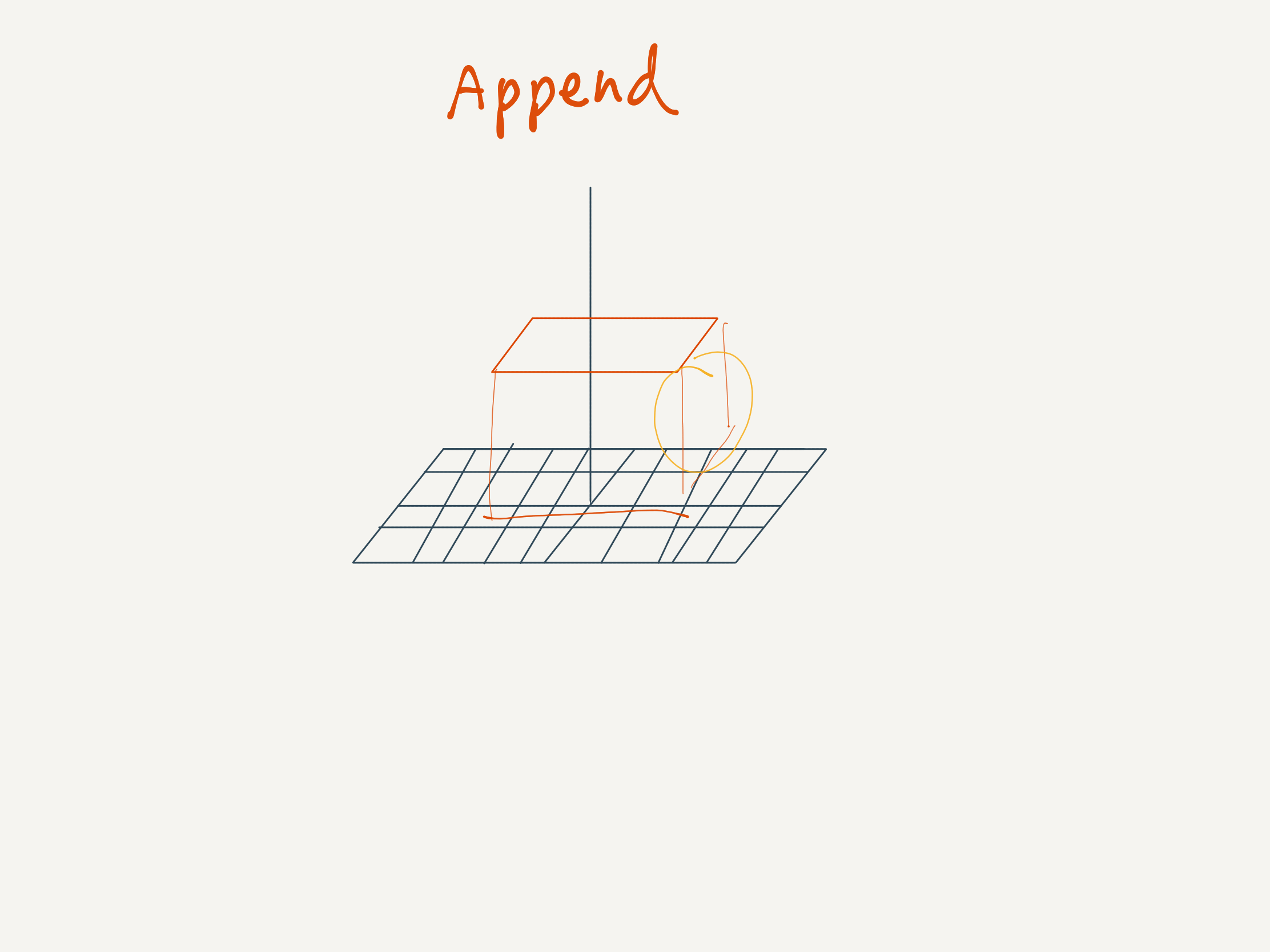

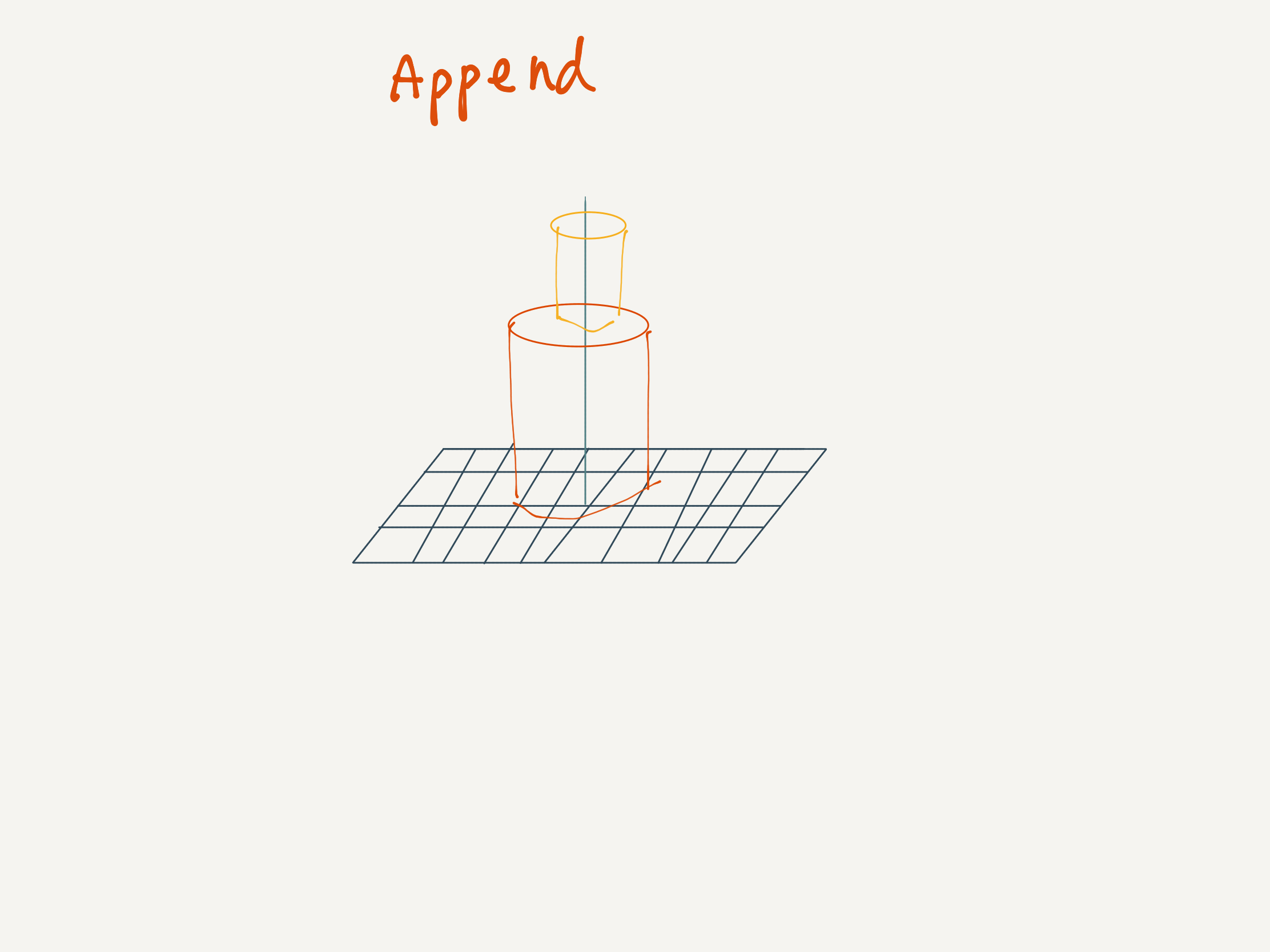

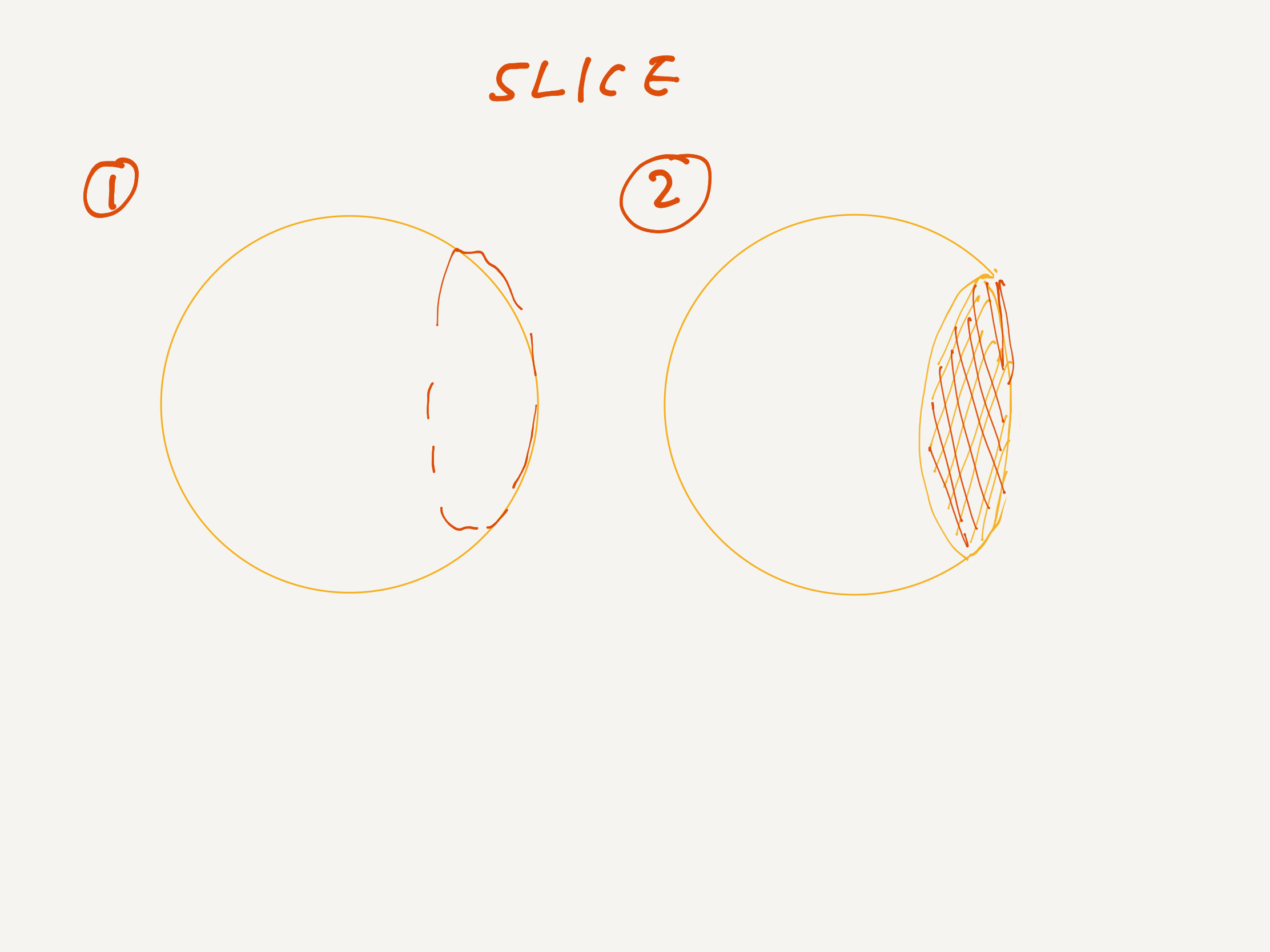

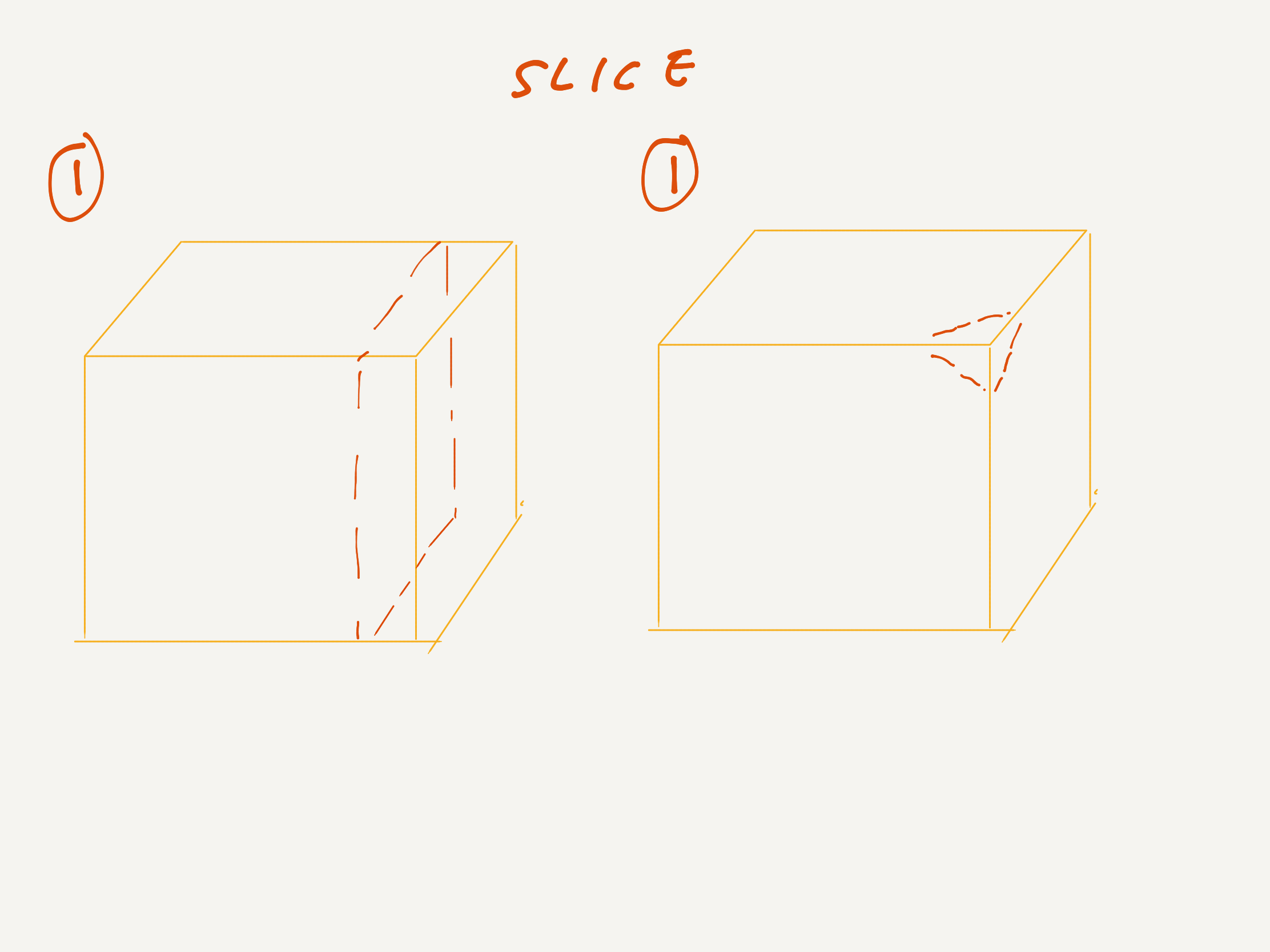

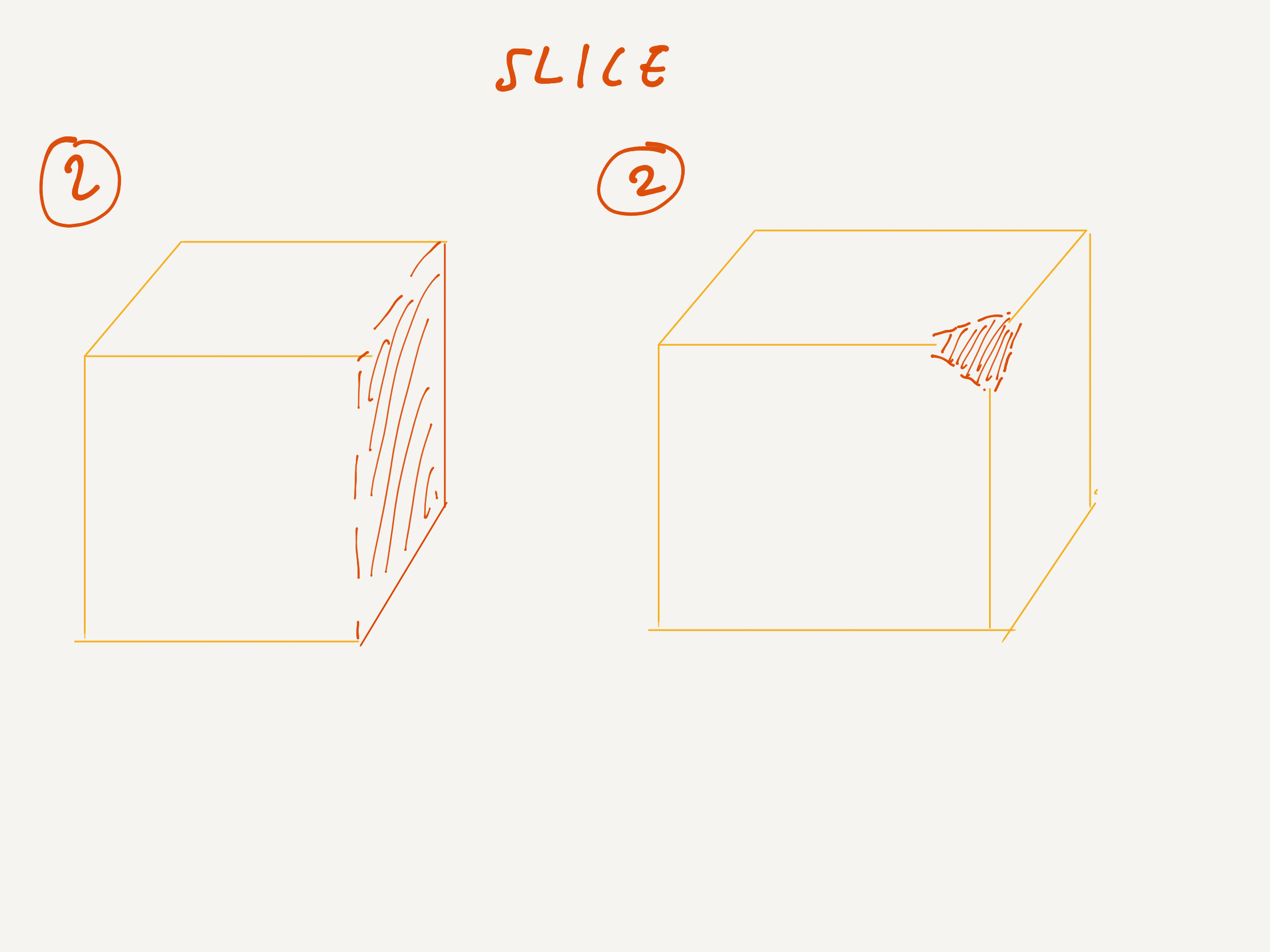

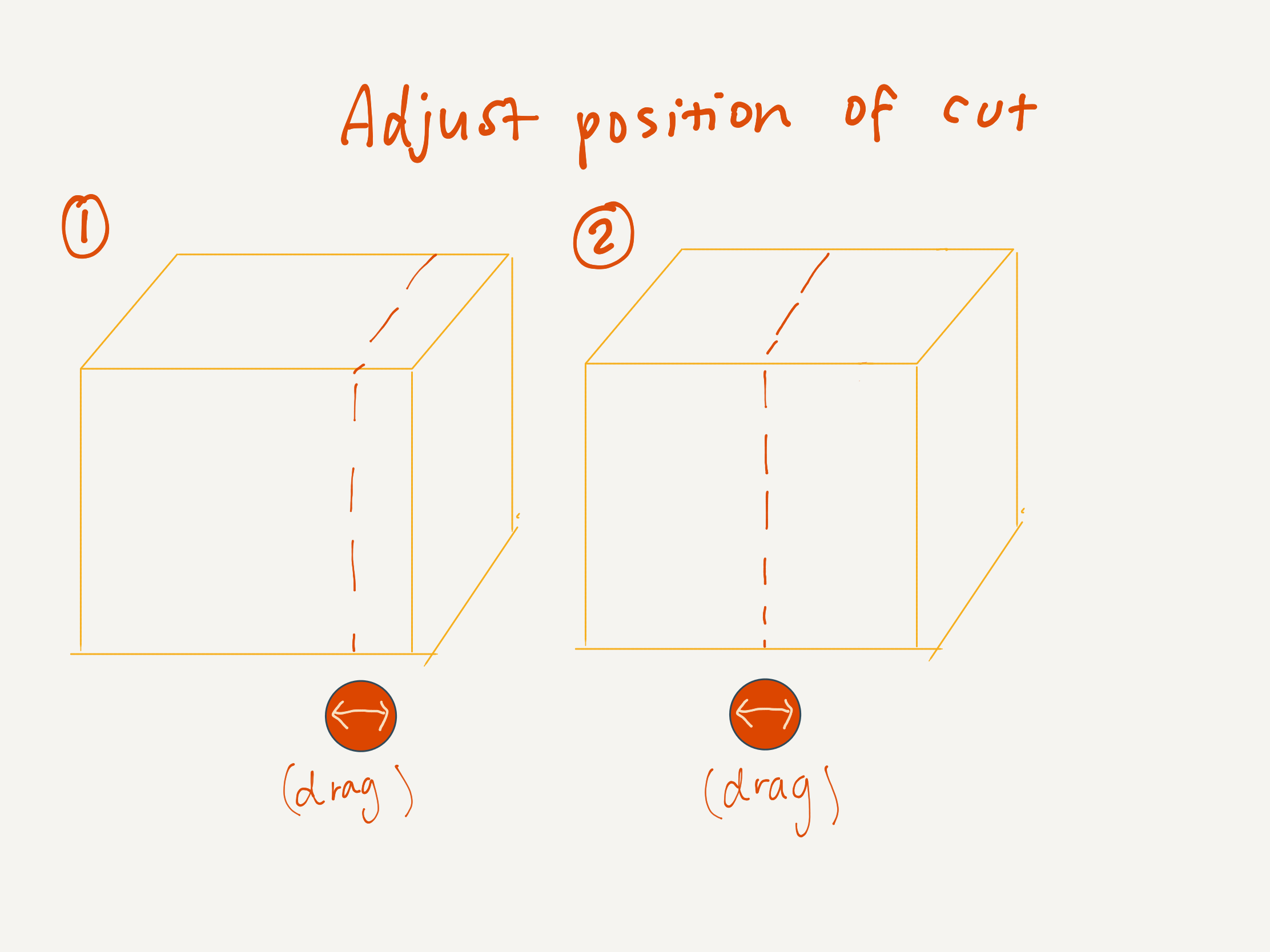

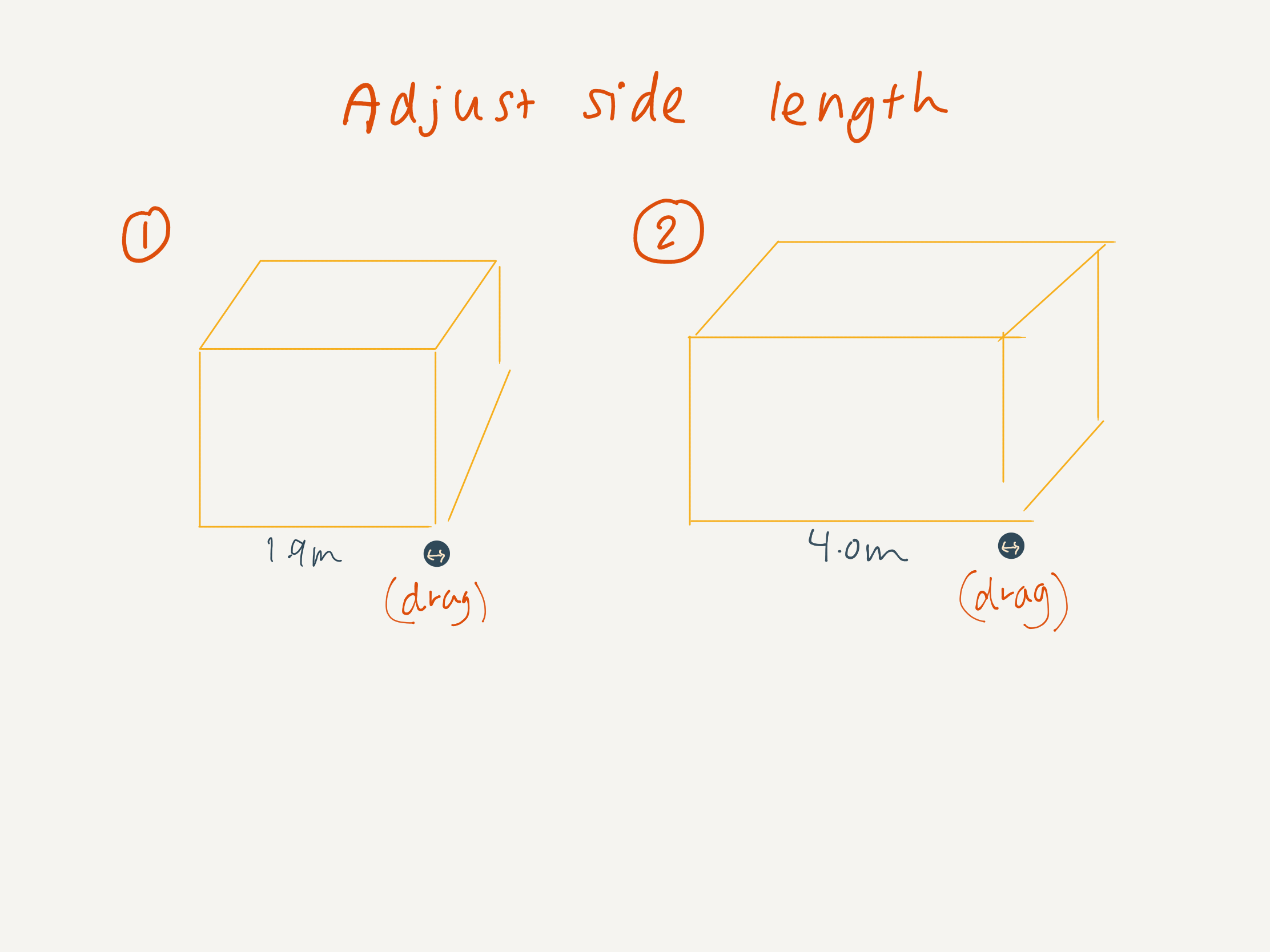

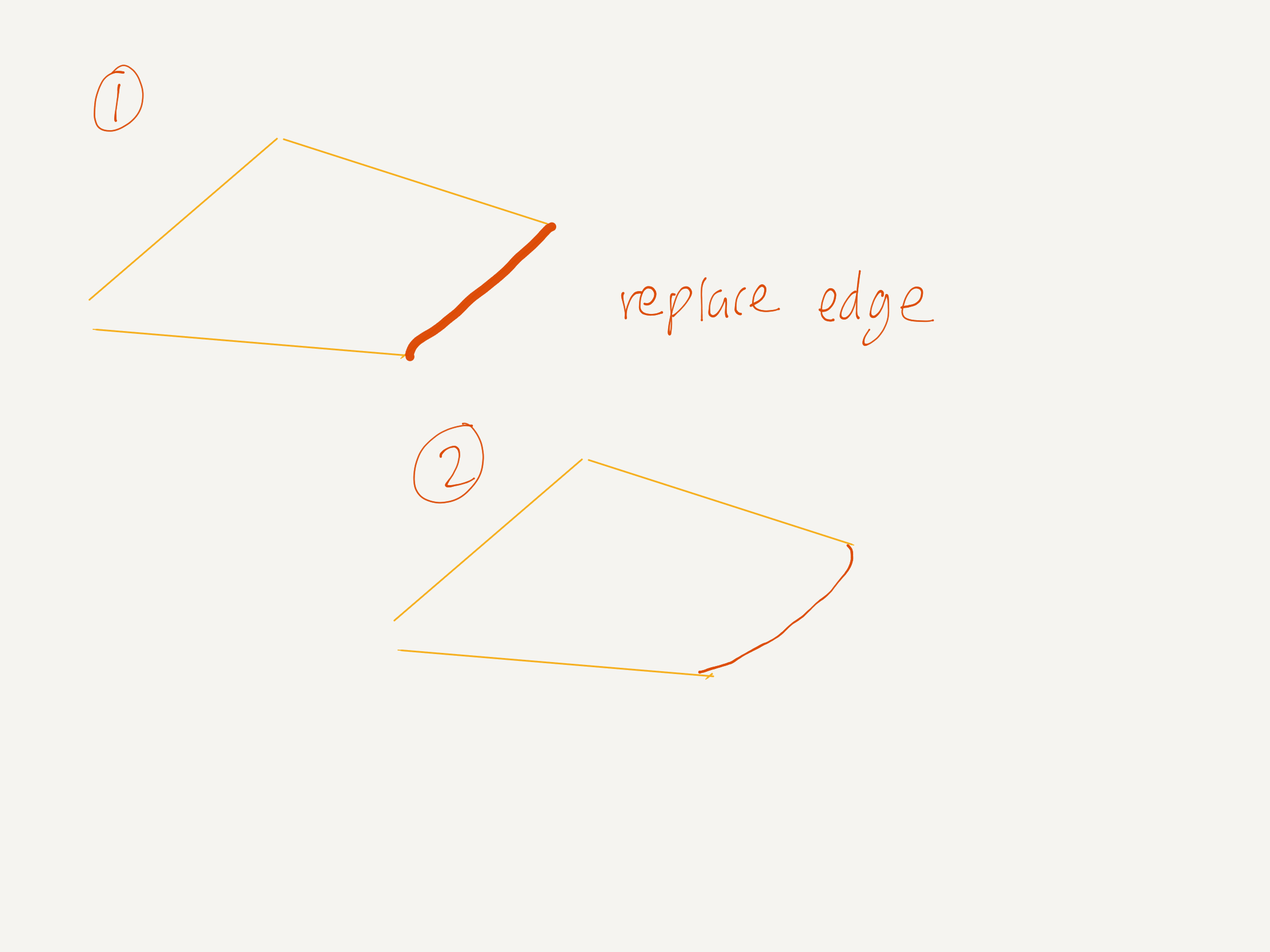

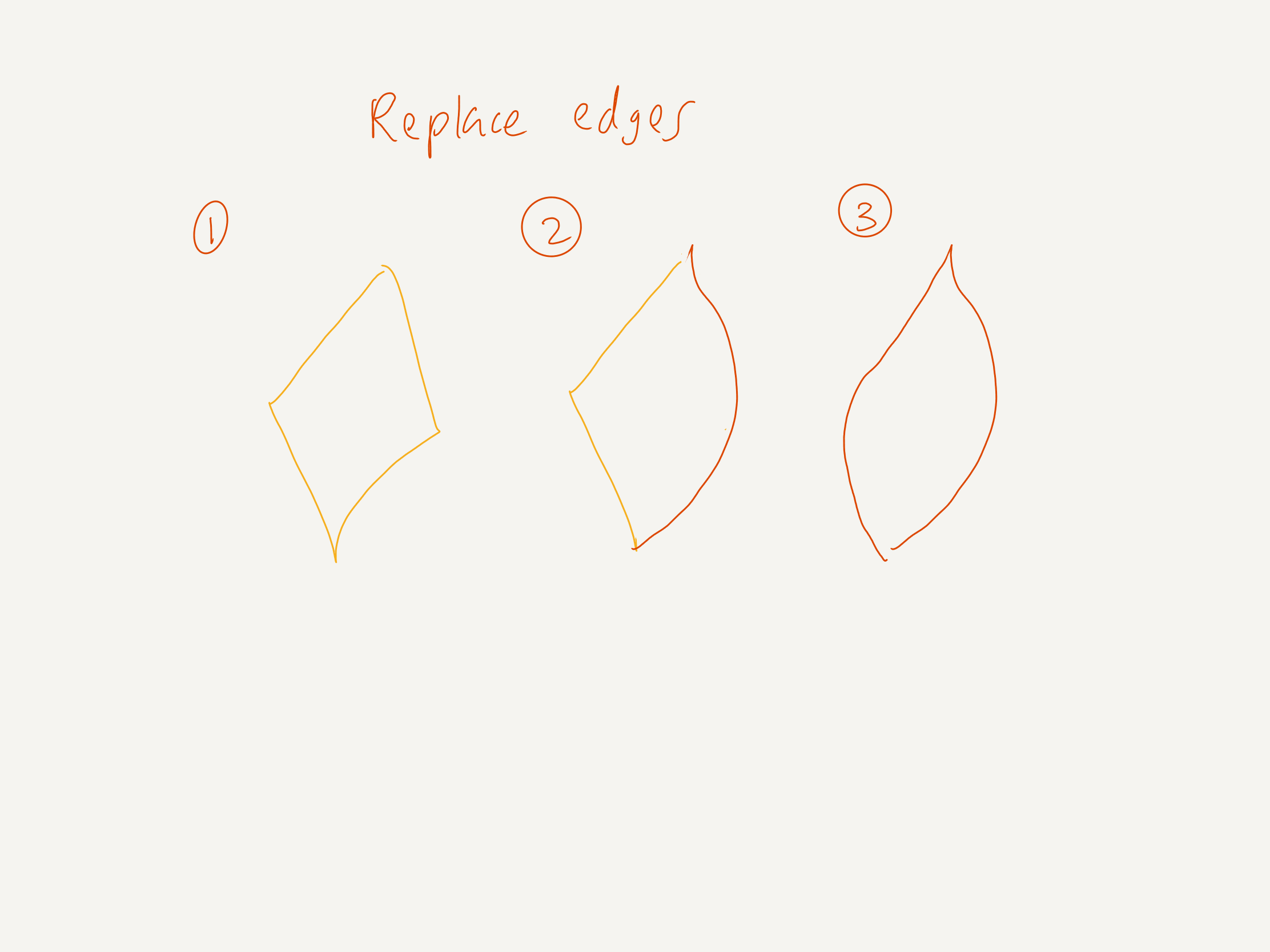

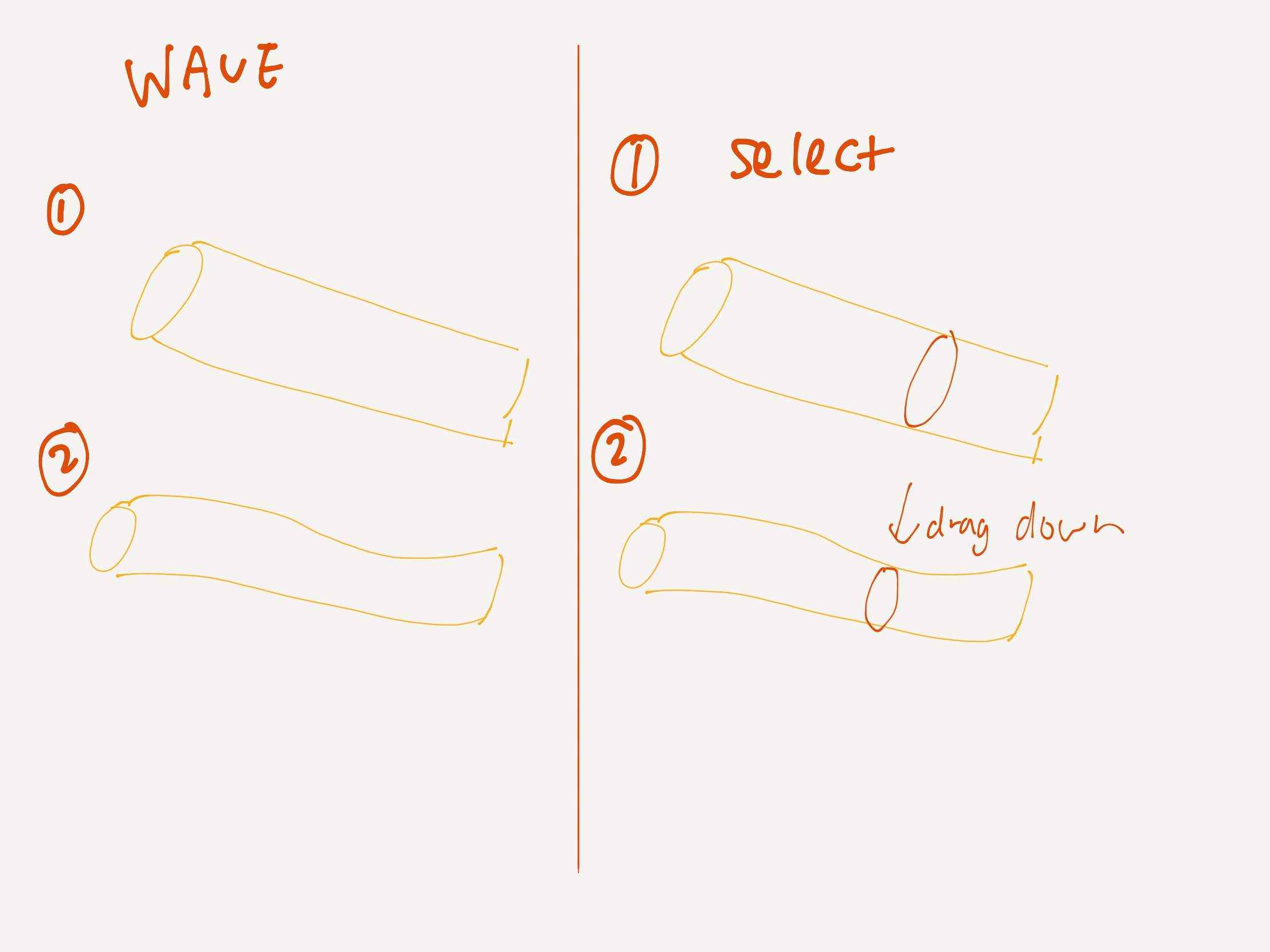

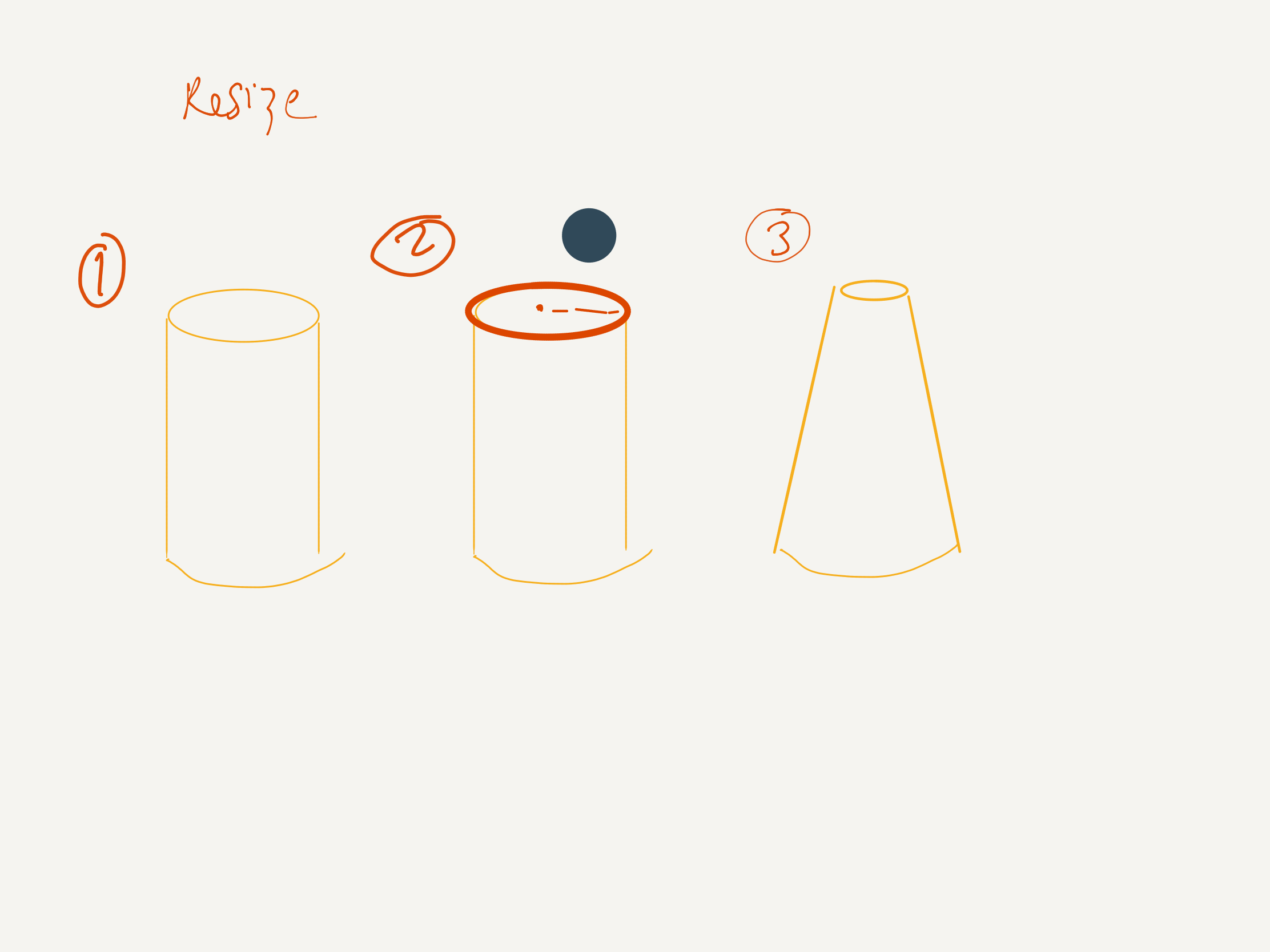

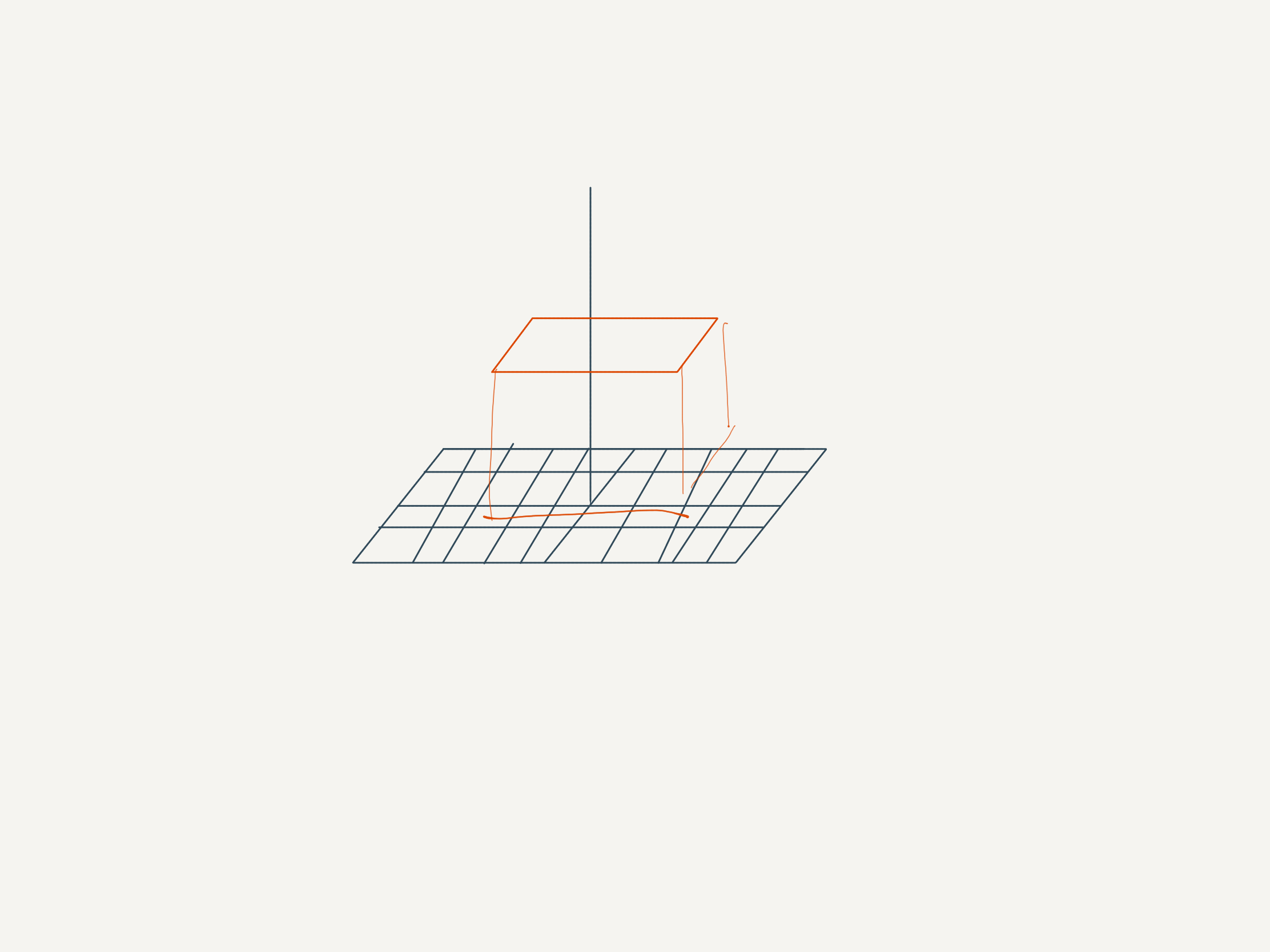

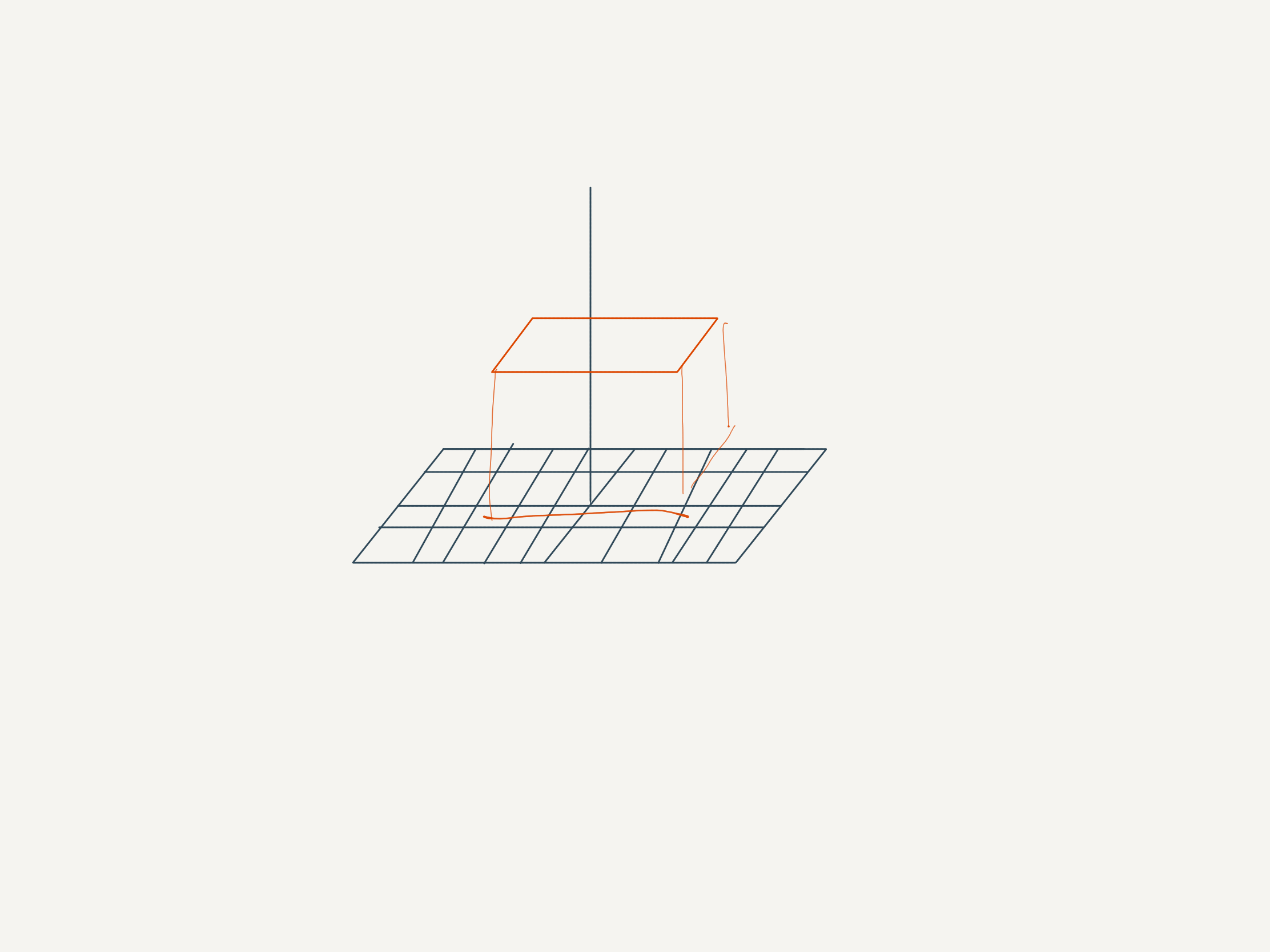

Taking inspiration a bit more directly from Think Kit, I had some sketches.

It’s not quite purely modeless editing, but it’s more modeless than having to memorise specific keyboard keys for editing.

What if you could just draw outlines of prisms and other shapes, and have them generated? Like how you can draw outlines of rectangles in Paper and manipulate them as objects.

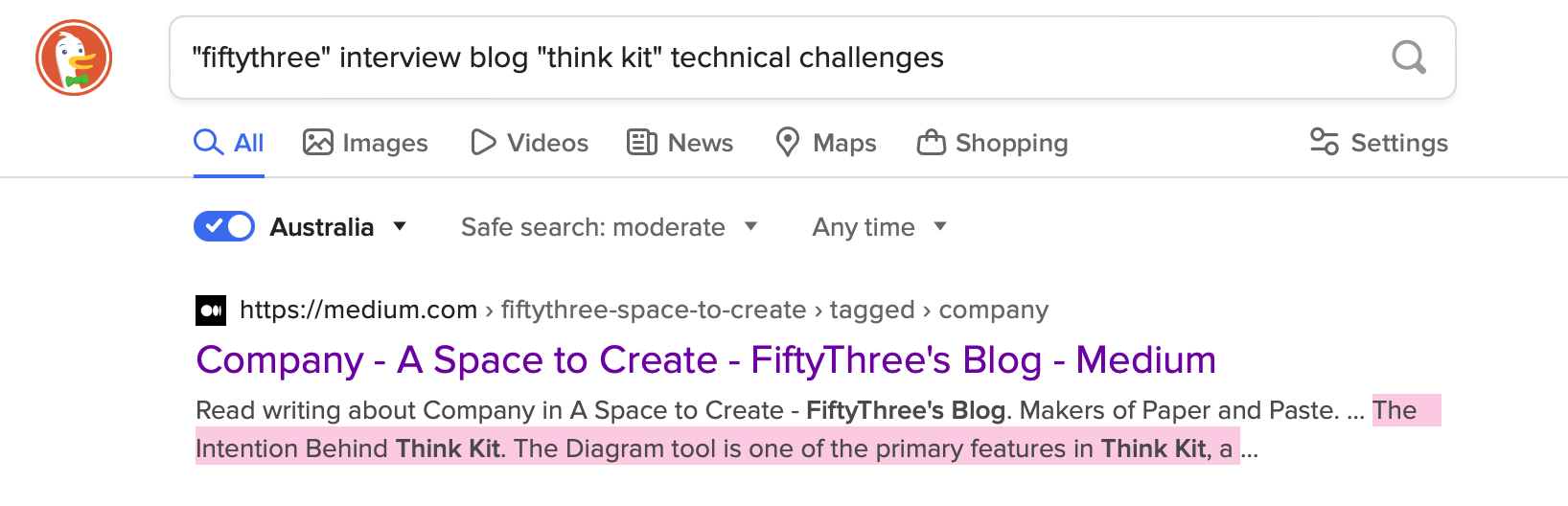

I distinctly remember that somewhere I read a write-up from FiftyThree about some of the technical implementation of Think Kit.

(It took so long — hours — to find. Couldn’t find it on even on archive.org. Saw it by chance after putting many phrases through DuckDuckGo and reluctantly Google.

Let me just say Medium has absolutely terrible indexing and discoverability.

I’m definitely saving this on archive.org now (you’re welcome!):

I remember that it detailed some of the challenges with recognising different shapes from points in space alone — for example, diamonds and ovals were quite similar. They got around this by also taking into account the speed at which strokes are drawn.

The Intention Behind Think Kit - FiftyThree

Detecting the intention behind a hand-drawn stroke is not easy. Imagine someone hands you a piece of paper. On that paper is a single curve — sort of circular, but with the left side a bit straighter than the right. Deciding whether that shape is a square, a circle, or something else entirely (say, a capital ‘D’) can be challenging for actual humans, possibly even undecidable.

Someone commented:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/think-kit-3d-building-future-speed-thought-james-corbett

https://web.archive.org/web/20160329011022/http://news.fiftythree.com/

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/20254440/recognition-of-handwritten-circles-diamonds-and-rectangles

https://www.recurse.com/blog/55-paper-of-the-week-worlds-controlling-the-scope-of-side-effects

https://www.recurse.com/blog/83-michael-nielsen-joins-the-recurse-center-to-help-build-a-research-lab

https://www.recurse.com/blog/104-a-new-essay-from-rc-research-fellow-michael-nielsen